PATRONS

Creating an illuminated manuscript like the Amsterdam Machzor is a long and costly process involving many specialised individuals. The patron is often an affluent person. In many cases, the valuable work is donated to the Jewish community and reflects the donor’s wealth, status and piety. Gifts may be donated to the community in commemoration of a person, an event, or to settle a score. The Amsterdam Machzor contains no colophon with which to identify its patron or its provenance, or the date it was completed. Based on the liturgy and the decoration, the manuscript appears to have originated in Cologne. It was presented to the Jewish community of Cologne, which had existed there since the early Middle Ages.

PROVENANCE

To judge from the many comments written in the margins of the Amsterdam Machzor by later users, the manuscript probably left Cologne in the Middle Ages. It is not until 1669 that the location of the Machzor can be determined for certain, based on two statements by Uri Fayvesh ben Aaron Halevi, a famous printer in Amsterdam. In 1669, he donated the manuscript – which he had received from his grandfather Rabbi Moses Uri Halevi – to Amsterdam’s Ashkenazi community to settle a quarrel. Since then, the Machzor remained in the possession of the Jewish Community of Amsterdam (NIHS). In 1955, the community lent the Machzor to the Jewish Historical Museum on long-term loan where it has often been on display until the recent purchase.

LITURGY

A Machzor is a prayer book for the Jewish festivals. Besides prayers, a Machzor also contains liturgical verse. These compositions recited on the various festivals are known as piyutim. Liturgy and piyutim may differ from one town to the other. The piyutim in the Amsterdam Machzor show that this Machzor adheres to the traditions of Cologne’s community. Moreover, the Amsterdam Machzor includes a haggadah, the order of service for the festive meal on Pesach, with its rituals, prayers and verse. This haggadah text includes piyutim which are still recited today. Later Machzorim (plural of Machzor) rarely contain the haggadah text, which makes the Amsterdam Machzor relatively unusual. After the thirteenth century, haggadot increasingly appear as separate volumes.

MATERIAL

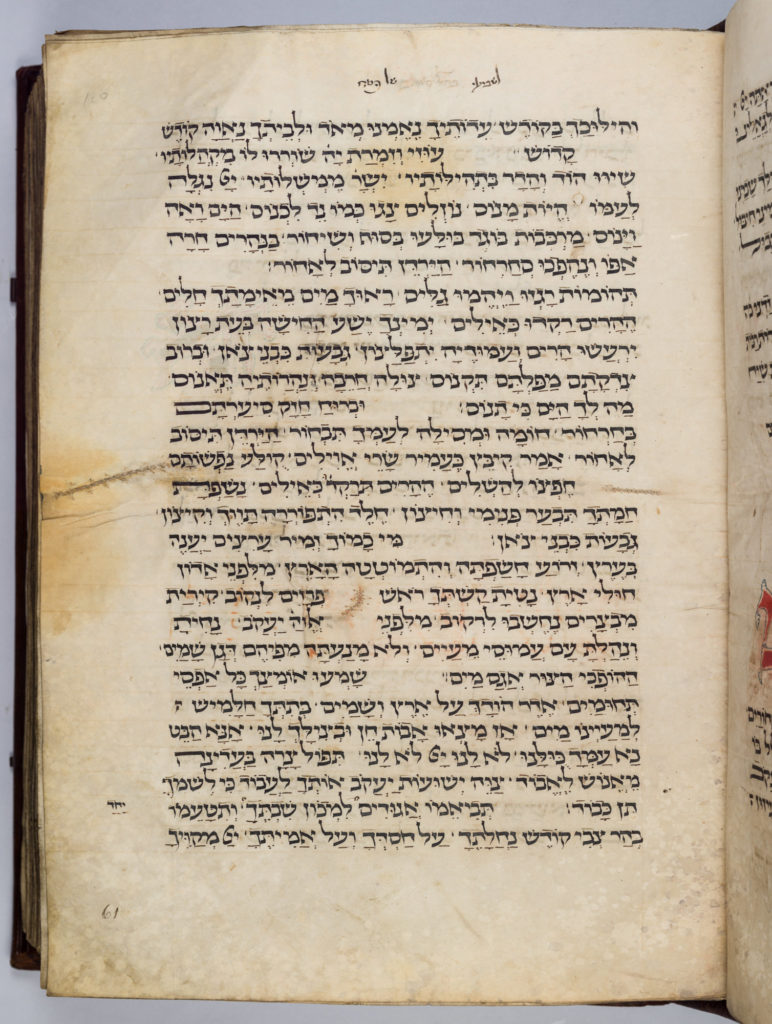

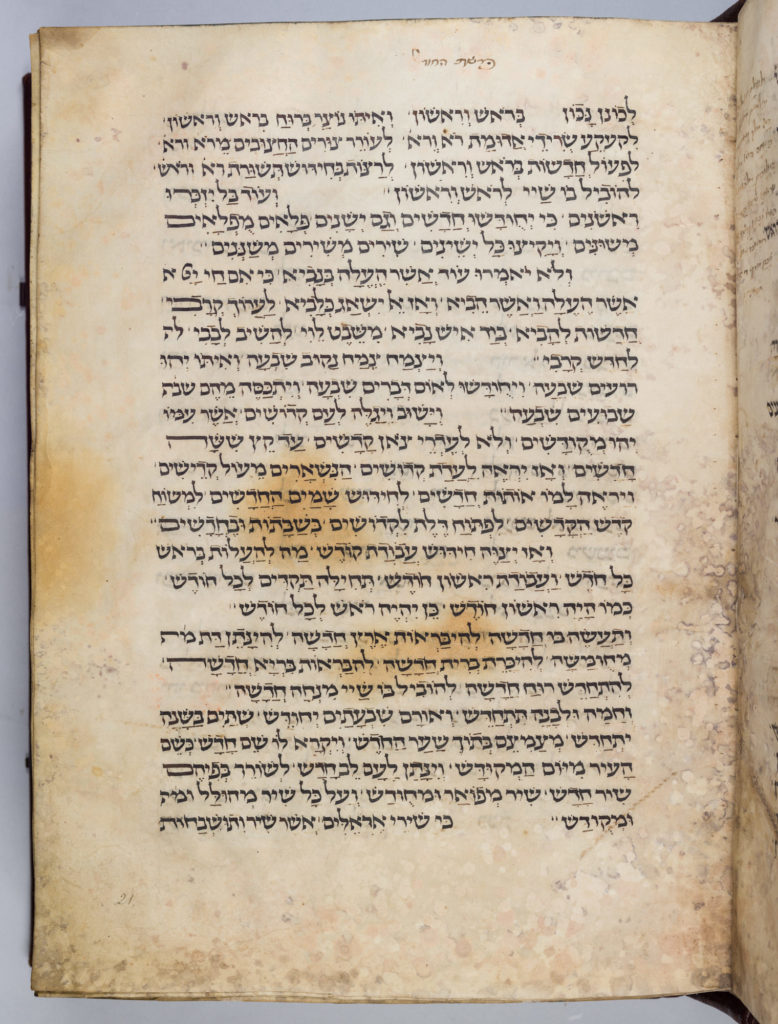

Apart from one missing leaf, the Amsterdam Machzor is complete. The book block comprises 331 leafs of double-sided coarse parchment. This is dried calf skin. To make it, the animal’s hide is soaked several times in water and lime, stretched on a frame and scraped clean of hair and flesh with a crescent-shaped knife. Then both sides of the skin are scoured to create two indistinguishable writing surfaces on either side. By 1260, artisans in southern Germany were able to prepare parchment well enough to make the flesh side and the hair side indistinguishable. Around the same time scribes developed new techniques for ruling lines. The Amsterdam Machzor reveals the use of different ruling techniques. It also contains occasional early repairs to the vellum.

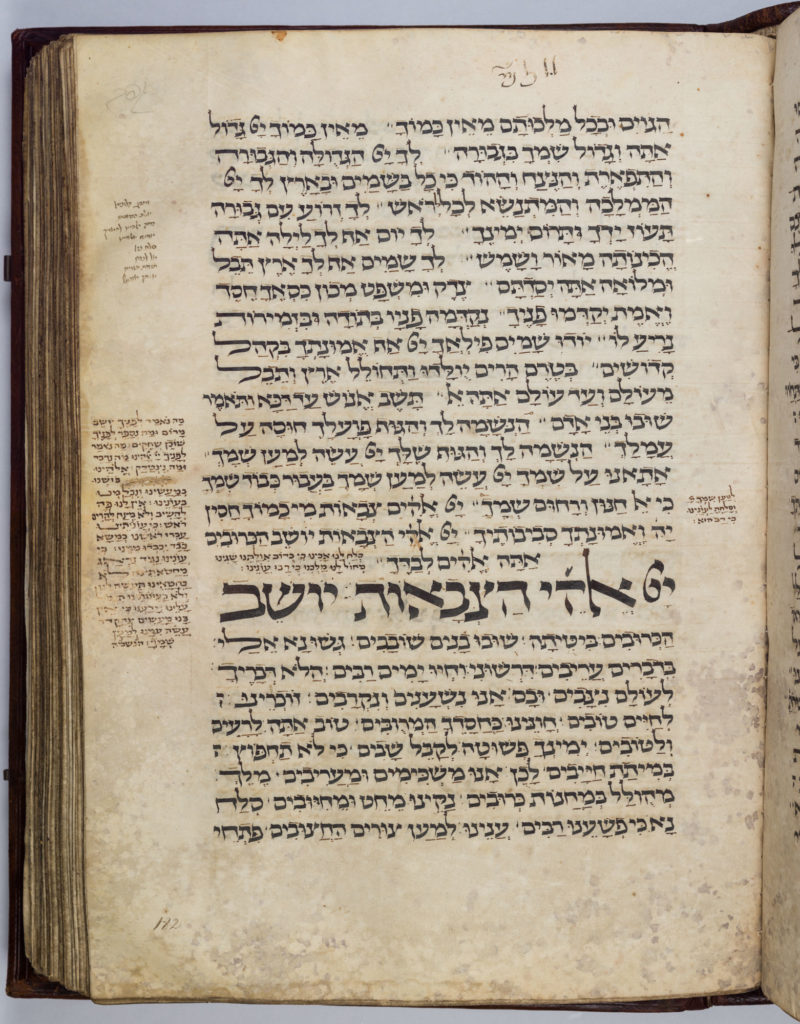

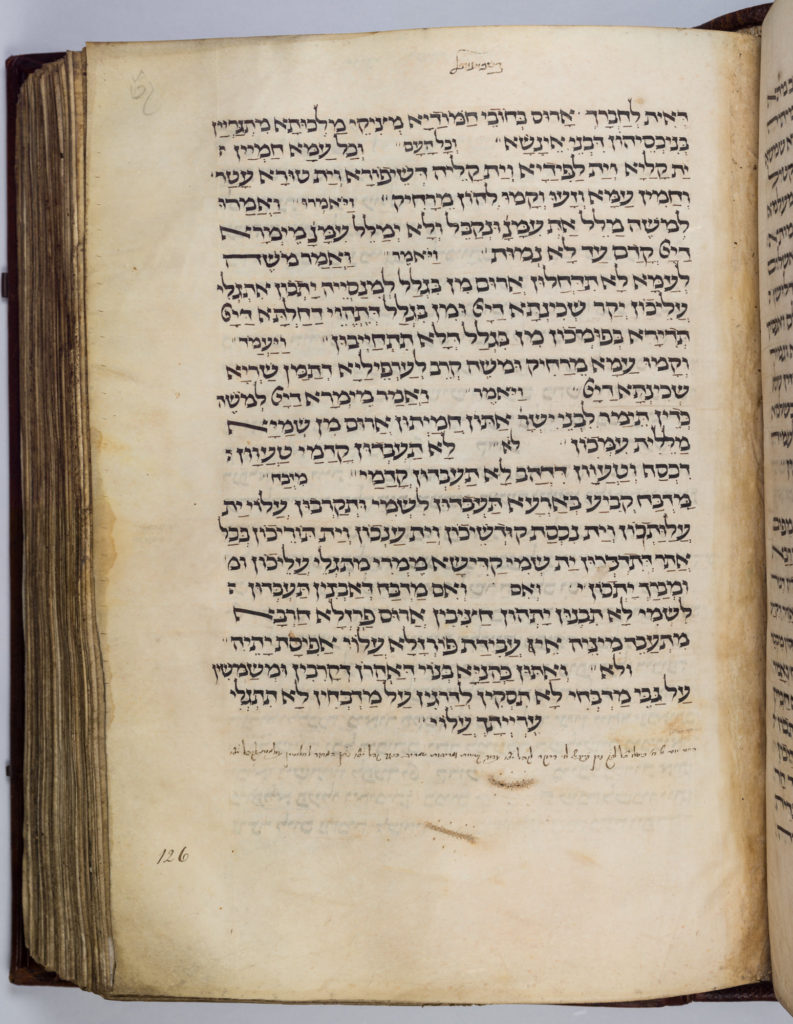

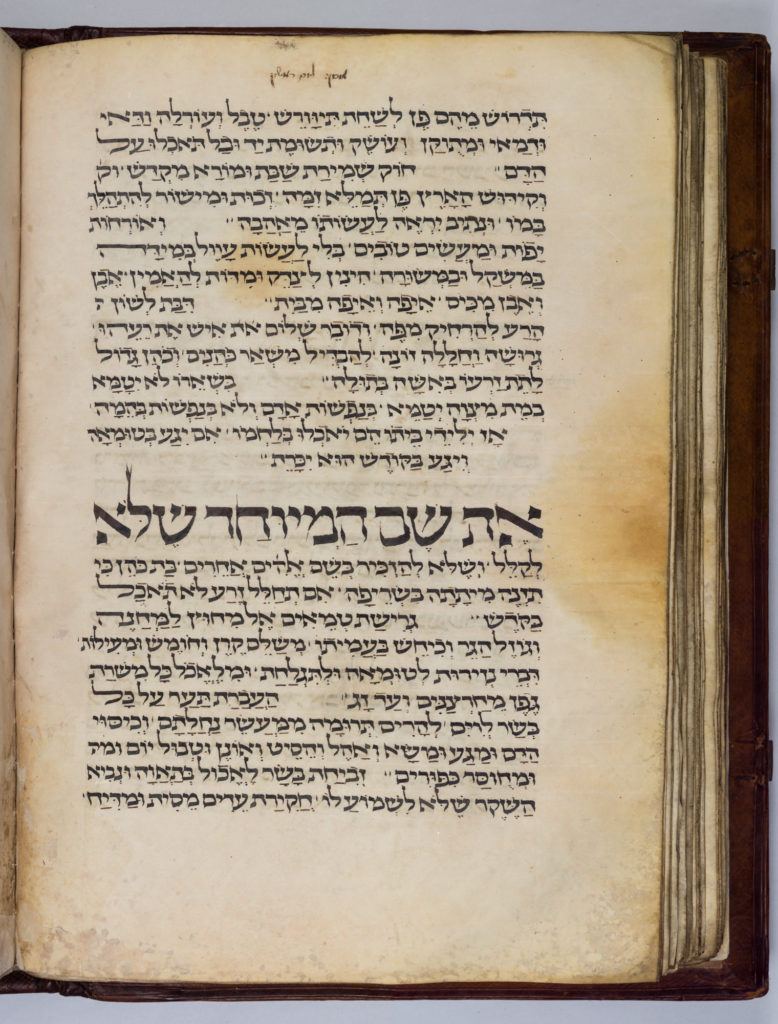

WRITING

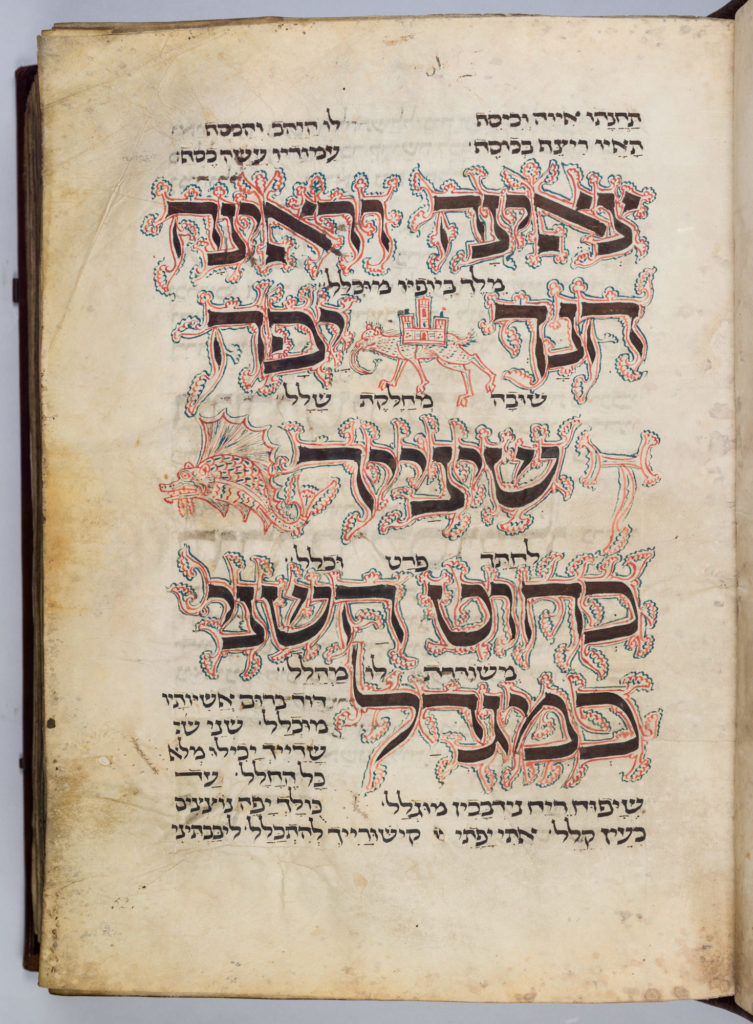

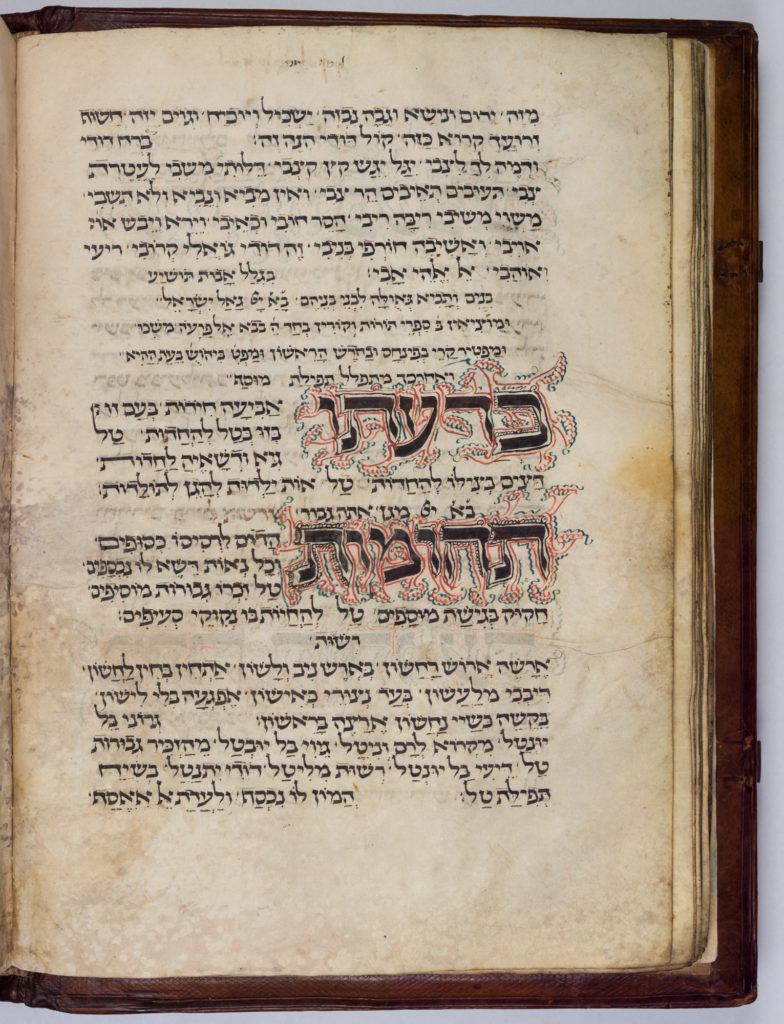

Handwritten Hebrew letters often reveal the geographical origins of the writer. Goose quills and reed pens are the two most commonly used instruments for writing, each producing a quite different style. Scribes of northern and western Europe prefer goose quills. These enable the writer to apply extra broad horizontal and thin vertical strokes. This gives Ashkenazi writing an almost Gothic appearance. Mediaeval scribes did not aim to create their own individual style. Yet while their ideal was to adhere to the stereotype, a wide range of styles can be found in Ashkenazi manuscripts. Based on the particular shape of these letters it is evident that the scribe of this Cologne manuscript originated in northern France. Indeed, northern France and the Rhineland formed a common cultural region.

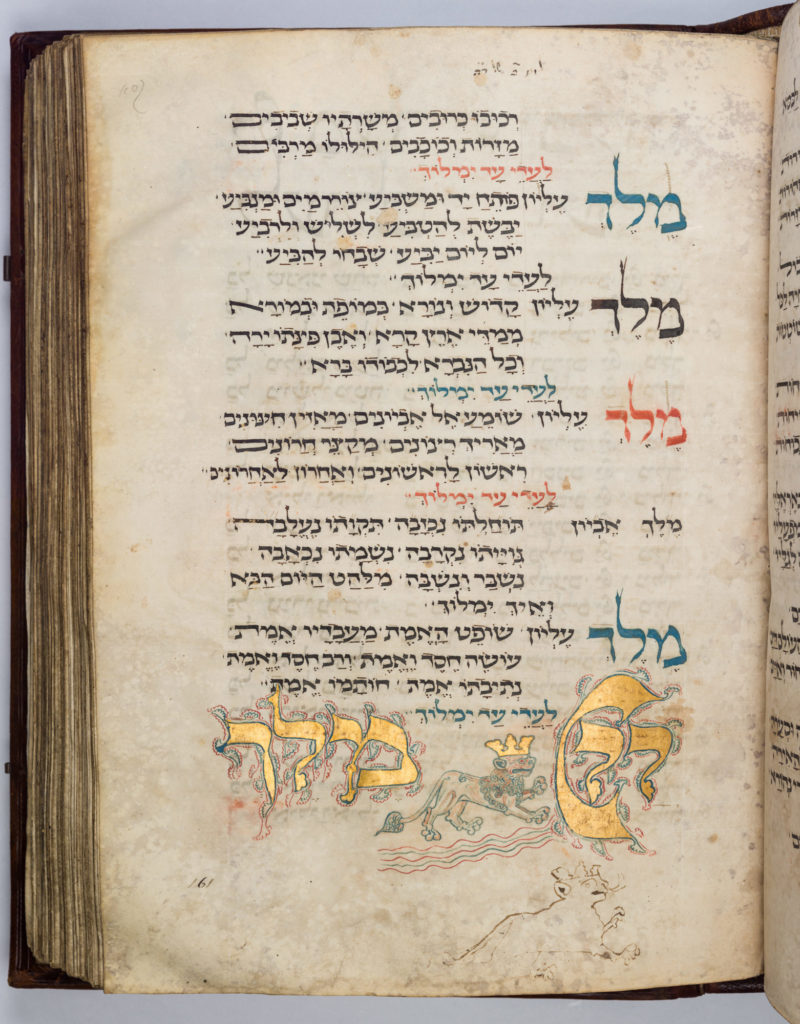

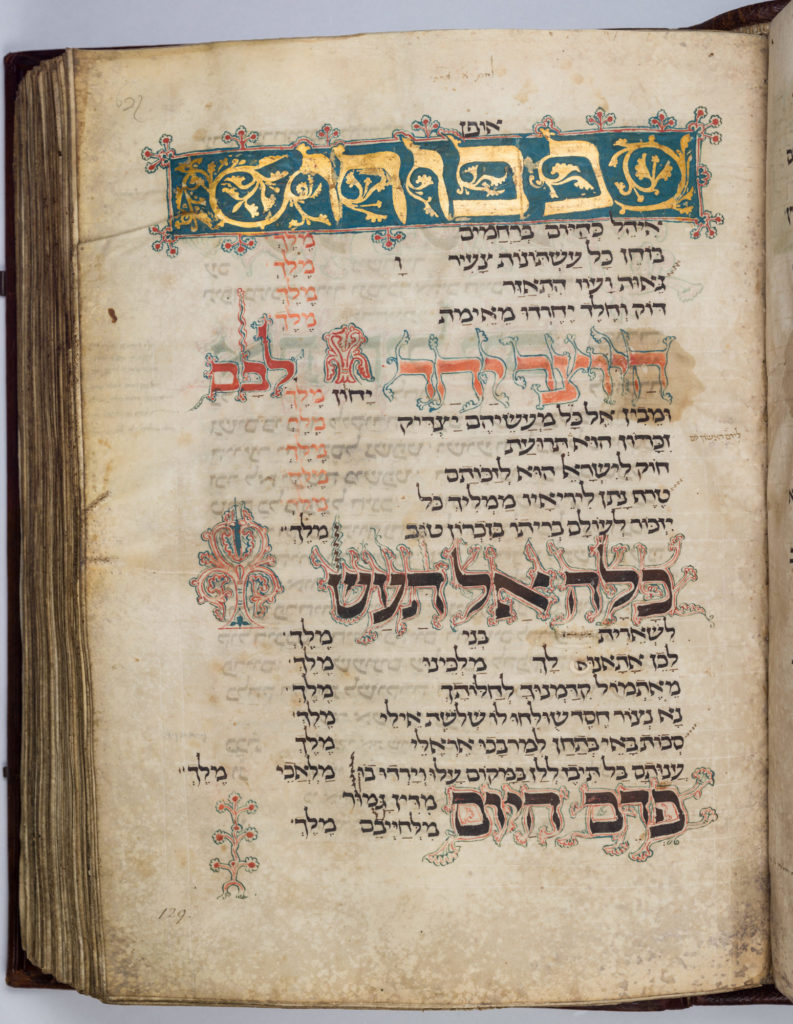

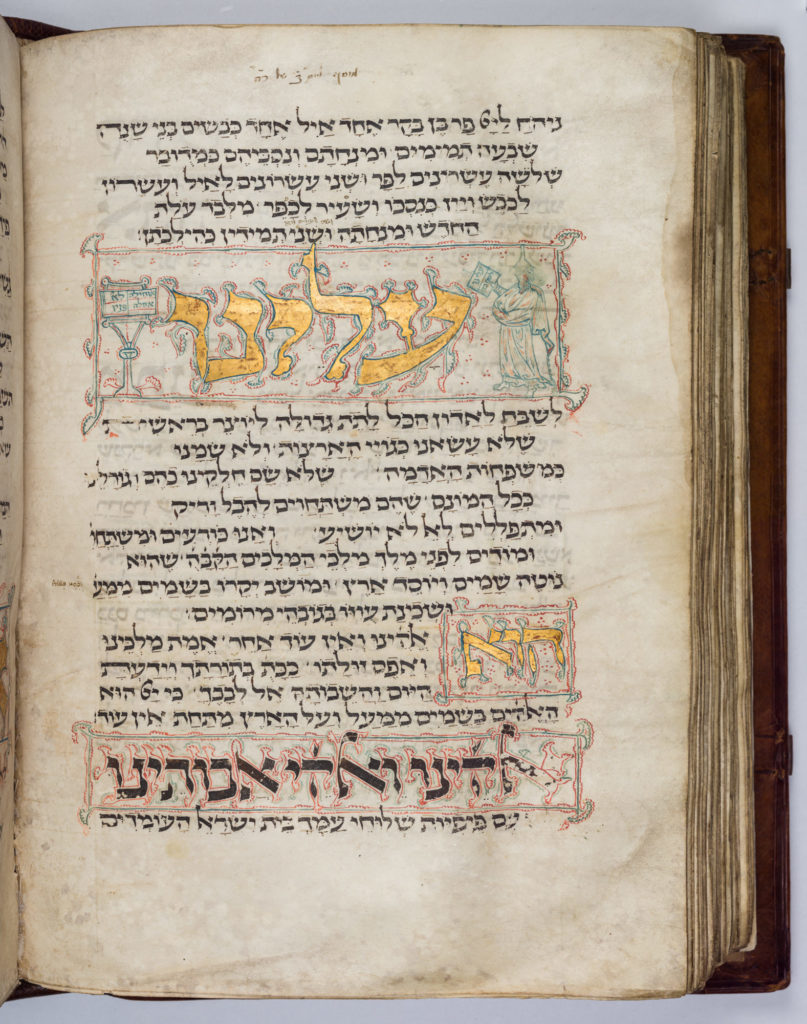

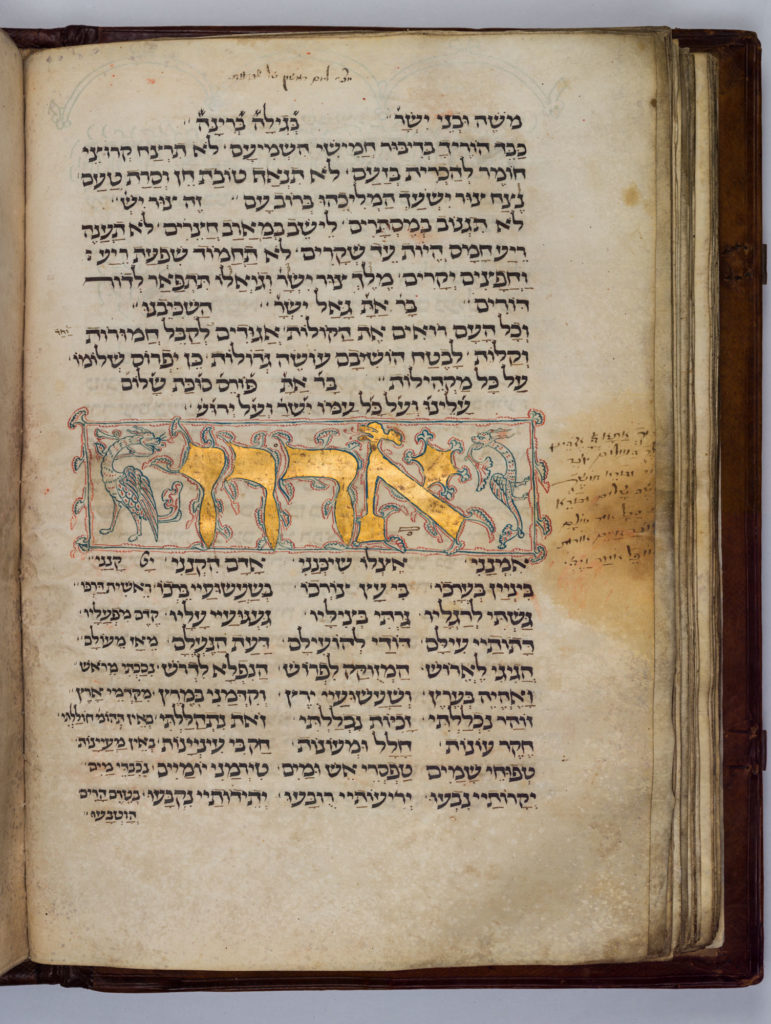

GOLD

Many of the miniatures in the Amsterdam Machzor are decorated with gold. This appears especially in the initials, attracting the reader’s attention and embellishing the volume’s splendour. To guild the letters, the illuminator would use either gold leaf or gold dust. The design of the letters is transferred to the page with a series of pin pricks or as a pen drawing. Then the vellum is prepared with gelatine glue and other materials, such as plaster. A wafer-thin layer of gold is then applied with a tweezer or brush. An omission was made in two places in the Machzor where the gold leaf was forgotten, showing the rust-brown ground layer. Finally, the gold is polished to give it a splendid sheen.

VIEW THE MANUSCRIPT ONLINE

Digital photography and website by Ardon Bar-Hama

2019 © All rights reserved